|

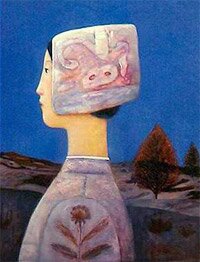

Portrait or Portrayal - Paintings by Xue Mo Melbourne, 2003 In the 20th Century, many Asian artists have sited, in the human figure, the portrayal and exploration of their own and their society?s identity and history and its changing relationship with other nations and a global culture. Chinese artists, returning to the figure in their art to convey ideas, break from a rigid tradition of landscape painting in place since the 11th Century, after figure painting, a strong aspect of art from the Han through to the Tang Dynasties, fell from favour. In this sense, the contemporary use of the figure represents a taking up of an old tradition and also a path to ?the modern?, in which the works of Mongolian born artist Xue Mo can be viewed. Along this path are Western cultural and artistic influences and their melding with her Eastern and female perspectives. Xue considers her work deeply affected by old Chinese culture, its traditional music, calligraphy and early portraiture. For enjoyment, she listens to Peking Opera, Beijing Jingyundagu and Mongolian Changge music, and the works ?Exquisite Beauty? and ?Flawless Beauty? were inspired by music by the Changge master, Ajabu. Xue, however, while working in her studio, usually listens to music by the western classical masters, Verdi, Mozart, Bach and Stravinsky. The texture of portrait brick paintings of the Han Dynasty and the line structure that lies beneath Chinese calligraphy of the Wei and Jin Dynasties are references for her works, as are the landscape paintings of the Ming and Qing Drynasties. These landscapes, Xue says, express ?a realm of high harmonious state of man and nature (nature has the same structure with man)?. To her, the essence of the ?old orient culture?s marrow? is this special relationship between man and nature, and one she seeks to portray in her work. Extending her Eastern perspective, Xue, as a student of painting and later a lecturer, amassed a large collection of Western art history books and developed a preference for the work of the European masters Piero della Francesca, Paolo Uccello, Bruegel the Elder and Holbein the Younger, and modernists such as Paul Klee, Mondrian and Morandi. The observation of their choice of subject, use of media and technique, composition and surface echo in Xue?s work. Identity - Personal and/or Cultural Xue?s painted portraits/portrayals 1999 to 2003 roughly divide into three groupings. The photo-realist works incorporate abstract elements, such as ?Portrait in the Mirror? 1999 (No.16) and ?Beautiful Peacock? 2002 (No.9); the flat fresco styled works reference early European painting surfaces, composition and lack of perspective, such as in ?Beautifulness? 2001 (No.5) and ?Sinking Beauty? 1999 (No.11); and in the ?Girl? series the character communicates through her face and body with the viewer, and interacts with her environment in a more naturalistic manner. If a portrait is defined as ?a likeness of a person, especially of the face, usually made from life? or ?a visual picture, usually of a person?, then are we to view Xue?s paintings as portraits, or as portrayals of ?person? or ?idea?? On viewing a painting of a person, or reading a description of their appearance and actions we automatically decide if they are ?someone? or based on ?someone?. Such is the human desire to recognize and know, to satisfy a curiosity, to place the person. Witness the continuing popularity of portraiture prizes, drawing large winning purses and competition between a growing number of artists, many not previously known for their portraits, and the ever-larger audiences. Looking at the other (person) tells us things about ourselves, seeing ?likeness? or ?otherness?. Xue, coming from Mongolia to live in Beijing, studying art, and as a Chinese woman traveling to America and other Asian countries has first-hand experience of both seeing and being ?other?. Whether a portrait is of an actual person or a fiction, the artist imbues it with identity and meaning. Beware therefore the human impulse to attribute an identity by reading meaning into a demeanour, facial features, mannerisms, a person?s costume and surroundings. This can play us false. Artists and actors have transformed cleaning women into creatures of myth and legend, the Greek Dianna the Huntress and the Christian Mary mother of Jesus Christ. In Xue?s portrayals, we are not told the identity of her women, whether they are fictional or real characters. Instead we are presented with an idea, an ideal, and perhaps, as in many portraits and portrayals, a portrait of the artist. Self Portrait or Portrayal That every portrait of feeling is the artist not the sitter is an idea worth considering. If portraits are self-portraits, then the sitter (or fictitiously created character) is the vessel containing the artist, created to play out different parts of the artist?s life. In Xue?s works she reveals herself, her thoughts, hopes and memories, not necessarily directly, but in aspects, metaphors and indications. ?Portrait in Mirror? is one such pivotal work in which the painter was seeking her innermost reality with a dark intensity. In the painting ?Sinking Beauty?, the open-faced woman, holding a flower indicating the traditional Chinese cultural relationship between woman and nature, has, according to the artist, opened new thoughts and dreams. East/West - Traditions of Beauty In the artist's own words, paintings from the ?Beauty Series?, exhibited in Melbourne 2002, invite the viewer to meditate on the qualities of virtue, serenity, benevolence and tranquility. Portraits of Chinese women expressed these qualities within a formal Western composition reminiscent of the Flemish and Italian Renaissance masters. This identification with European portraits is reinforced by the mystery surrounding the women. They are not named. We can only guess as to their identities by observing their dress, demeanour and their artist-attributed qualities. The only other hint of the sitter?s identity is perhaps the landscape beyond. Although many Renaissance portraits are known by their sitter's name, we now no longer know or understand the relevance of the original intention of artist for the painted portrait or know anything of the individual and therefore view those by Piero Della Francesco and John Constable much in the same manner in which we look at Xue?s paintings. In the absence of not knowing who they are, we can instead know what they are, what they convey. These vessels for Xue?s celebration of classical Eastern beauty, idolizing ?woman?, and her homage to Western art tradition, take her works outside the constraints of time and era. Timeless beauty resonates across cultural divides, and the act of painting captures the woman, fixes her in time, at an age, and with a beauty that will never fade. Each portrayal by Xue has her own narrative, her own fiction. The clothes and adornments alone build and confer the identity. Some items denote social status, racial background, others cultural tradition and an aesthetic. It is these, rather than the woman and her figure through gesture, action or surroundings that carries the portrayal in this series. ?Noble Beauty? 2002 (No. 28) in serene profile has her hair bound up in a textile, 16th Century European style, and is dressed in rich red cloth up to her ivory neck. Against a somber impenetrable background the young woman glows. The classic head and shoulder pose composed of head, neck and body; forms simplified by restrained dress, lack of adornment, jewelry or patterned fabrics. No foreground to separate the figure from viewer, no object or element for the sitter to interact with, nor clue of landscape with which to locate the woman. Painted one year earlier, ?Mongolian Beauty? (No.10) depicted in similar compositional terms a young woman also in red attire. The high-necked tunic, a headdress encrusted with medallion forms and beaded train echo the line of her plaited pigtail, and large hoop earrings locate a north eastern ethnicity. Past the elaborate forms recedes a road across a sparsely vegetated plain giving a sense of open space. However the lack of interaction between the figure and the background (it could be a painted flat backdrop in a studio) only adds to the iconic nature of the painting. Whether it is the contrasting limestone and green terrain in ?Exquisite Beauty? (No.7) or the cultivated and treed fields ?Blue? (No.19), this is an aspect shared by all the works within this series. A Chinese woman, painted in a western portrait style, is the reverse of the European Impressionists who sought to incorporate Asian cultural and artistic influences in their 19th Century paintings. Contemporary cross-cultural development and appropriation within the arts has a long and creditable tradition. Artists for centuries have moved from court to court, between church, private patron and state, and from country to country. Encouraged to find new markets and audiences for their skill and ideas, they are curious to discover other sources of inspiration and to learn from a wider pool of knowledge. Expression of Change Art, a key manifestation of a culture, is an ideal site in which to explore the issues around a changing personal and national identity. In defining or charting a changing identity, one that is subject to nature and societal constructions of age, life events, family relationships, environmental economic, political and global influences, can be expressed in playing with histories and stories and in the case of Xue, as like many Asian artists, east and west cultures merge. For her, the figure is the site for this cultural contrast, the exchange and merge. Here she sites woman?s multiple roles and identities in society, which in common with women around the world, they have been required or chosen to don or discard. Xeu is one of the few Chinese artists whose work is shown commercially in Australia, a country known to her only via the television tourism channel and the net. As a counterpoint to this, most visitors to her exhibitions will be seeing a contemporary Chinese artist's work for the first time, and their knowledge of Chinese culture will be a mixture of Kung Fu movies, a local restaurant and an archeological blockbuster exhibition. Xue?s portraits and portrayals add to this experience on a personal level and may lead visitors to view Chinese as not so different, not so foreign. Openness to Western Influences - A Parallel Xue?s articulation of personal aspirations for international co-operation and for a better life for the Chinese people occurs at a time when China is opening itself to more interaction with Western culture and economies. An expression of this evolution may be reflected in Xue?s ?Girl? portrayals. The young women of this series may still epitomize beauty but their heads, limbs and bodies are not longer two-dimensional. Free of headdress and costume ?Girl Free Hand Over Her Head? 2003 (No.18), she leans against a wall in a natural air. Her body in the unconscious spirit of youth reclines on a couch or bed, her short skirt riding up to expose smooth legs or a strip of midriff. Xue has not distanced us from the girl or diminished her scale in order to portray more of her body; rather she has folded, draped and opened her figure. The shift in mood and composition is accompanied by the introduction of the third dimension, space; and the modeling of the figure?s form contributes to the natural modernity of these works. They are painted with economy; minimum external distraction and detail are required to describe the body?s contours. Xue?s restrained palate, here of rosy flesh and contrasting blue, mauve and warm cream through to grey and black, focuses attention to the essence of the spirit of the girl. Dressed in contemporary clothing the girl is without a national costume of identity or tradition, and firmly located in the present. Approaching adulthood, her gaze is open and confidant, the girl is a different archetypal identity to those in the ?Beauty? series. |

? |

Xue Mo, Blue Series 4, 2002 |