An international force in the contemporary art scene, Chihuly?s studio in Seattle has launched the prolific artist and his chosen medium to worldwide critical acclaim; and more than 200 museums, from Israel to Taiwan ? and closer to home, the Denver Art Museum ?permanently display his work. There are another 100 public installations in settings as diverse as the Atlantis Resort in the Bahamas and the Atlanta Botanical Garden, all of which make Chihuly?s prominent presence in Beaver Creek a real treat for globetrotting guests and art-loving locals.

Heart of Glass

Born Sept. 20, 1941, in Tacoma, Wash., to George and Viola Magnuson Chihuly, Dale Chihuly at first had no desire to continue his formal education after graduating from high school in 1959. His only brother, George, had died in a naval aviation training accident in Pensacola, Fla., in 1957, and his father suffered a fatal heart attack the next year at the age of 51.

But Viola Magnuson Chihuly convinced her son to enroll at the College of Puget Sound, now the University of Puget Sound in Tacoma, and successes there led him to transfer to the University of Washington in Seattle to study architecture and interior design. After taking time off to travel in Europe and the Middle East, Chihuly ultimately earned a B.A. in interior design from the University of Washington in 1965, the same year he discovered the magic of glassblowing. He began a lifelong exploration of the art form that led him to revolutionize how it is produced by artists and viewed by the public.

?One night in 1965, I melted a few pounds of stained glass in one of my kilns and dipped a steel pipe from the basement into it,? Chihuly says. ?I blew into the pipe and a bubble of glass appeared. I had never seen glassblowing before. My fascination for it probably comes in part from discovering the process that night by accident. From that moment, I became obsessed with learning all I could about glass.?

The next year, Chihuly worked as a commercial fisherman in Alaska to earn money for graduate school; but he wound up landing a full-ride scholarship to the University of Wisconsin, where he studied under studio-glass movement founder Harvey Littleton in what was the nation?s only glass program at the time. The next year, Chihuly earned a master?s degree in sculpture and promptly enrolled in the famed Rhode Island School of Design in Providence, where he earned a master of fine arts degree in ceramics; and in 1969, he established the glass program at the school, teaching full-time there and working with some of the most important names in the growing glass-art movement for the next 11 years.

In 1970, during a student protest of the Vietnam War that shut down the Rhode Island campus, Chihuly and a student came up with the concept of an alternative school in the Pacific Northwest; the Pilchuck Glass School, which would dramatically shape the glass movement for years to come, was born 60 miles north of Seattle in 1971. It was there that Chihuly?s first major environmental installations began to turn heads in the contemporary art world.

The nation?s bicentennial, 1976, was a watershed year for Chihuly ? one of both personal tragedy and professional triumph. He was severely injured in a car crash in England that left him unable to see out of his left eye, forever robbing him of depth perception and the ability to work directly in the very hands-on and intricate medium of glassblowing. But that same year, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York acquired three of the pieces from his Navajo Blanket Cylinder series, establishing Chihuly not just as a leading force in the world of glass art but also as a major museum-quality artist of significance to the broader world of contemporary art.

The accident turned out to somewhat providential in that it led to Chihuly becoming a conceptual conductor orchestrating a creative dance by a team of glass artists. In this way, Chihuly is credited with revolutionizing the studio glass movement, expanding it from the solitary artist laboring on smaller, delicate forms to major collaborative efforts by many artists coming together to shape massive installations comprised of hundreds of blown pieces.

Fortunately he didn?t give up the medium entirely, because technically he can?t do that sort of work anymore, but he had all these wonderful ideas for changing glass from a craft to a high art form. ?He started doing these paintings for inspiration for a piece or a project, and then he had some very talented younger artists working with him and they would all get together and ? he?d be the conductor and he?d help them create these wonderful ideas going into some more monolithic-sized pieces.?

Far from diminishing his work, the collaborative approach enhances Chihuly?s ability to oversee his artistic passion. ?Even though he doesn?t blow any of the glass himself, the ideas come from him, the creativity comes from him. ?And he signs off on everything; it?s not as if he just has hired guns that he passes things off to.? Prolific and dynamic, Chihuly has established collaborative, large-scale studio works as his trademark.

?Having the support and skills of a large team can be tremendously gratifying,? Chihuly says. ?I feel very fortunate to be able to have such talent at my disposal, especially now that I am involved with large architectural projects and installations. Glassblowing is a very spontaneous, fast medium, and you have to respond very quickly. I like working fast, and the team allows me to do that.?

From Craft to High Art Form

Besides forever changing how glass artists work, Chihuly is widely credited with reshaping the public?s perception of what glass art is and how it should be viewed.

?It?s pretty exciting to see the whole changeover right now,? says Trevino. ?It?s in our lifetime and we get to see all of this growth in the modern glass movement; it?s quite a treat. A lot of those movements are way before our time. And this is going from a craft form to a high art form; that?s a big switch, as well, in the art world.?

But Chihuly, who in the 1990s saw his pieces being included in the collections of more and more museums worldwide, says he isn?t that concerned with how his work is viewed by the mainstream, contemporary art community, but is far more intent on how his worked is viewed by the public.

?I don?t try to please the art world,? Chihuly says. ?I care about getting my work out where people can see it, whether it?s in a museum, a public building, a resort, or whatever. Whether people think it?s art or craft is not important to me. If it gives people pleasure, if it makes them feel good, that?s what counts.?

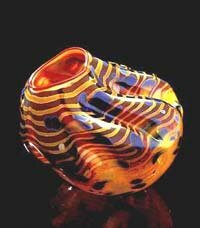

One indicator of how Chihuly has helped to transform the public?s perception of glass art is his influence over Italian glass masters, such as Lino Tagliapietra, whose intricate work can also be found at PISMO?s Beaver Creek gallery. Prior to meeting and beginning to work with Chihuly as a gaffer in the mid 1980s, Tagliapietra was much more of a classical glass artist, creating beautiful but functional pieces, such as goblets and vessels. In fact, says Trevino, Tagliapietra was one of Chihuly?s mentors. The Italian?s incredible skills as a glass artist had been handed down from generation to generation and therefore rooted deeply in tradition ? and Chihuly wanted to show the Italian masters what was possible when glassblowers broke with that tradition and expanded their creative horizons.

?So he brings Lino over (to the United States), and Lino has seen all of these young artists and wants to cultivate the talent over here, so he has released all of these secrets that were passed down to him to these other artists, and so the glass movement has just taken off from there."

Beginning in the late 1980s, Chihuly worked with Tagliapietra on several Venetian series, collaborating into the mid-1990s. That Italian influence continued in 1995 in a series of public glassblowing sessions from Iceland to Mexico culminating in the next year with the hanging of 14 Chihuly chandeliers at various sites around Venice.

That kind of public accessibility is what Chihuly means when he talks about giving pleasure to the people. Chihuly in the Light of Jerusalem 2000, the artist?s largest and arguably most ambitious project to date, was comprised of 17 separate installations set in the walls of an ancient military fortress. Intended to celebrate the millennium, the installation, which has since been removed, is still talked about to this day ? not just in art circles, but also by the general public lucky enough to have seen it.

You now see a lot of people who are just now starting to get familiar with glass as an art form, ?And now, thanks to Chihuly for the most part, it?s really going out to the general public and they get to see all of these big installations at museums and hotels and botanical gardens and look at it in a whole new light, because beforehand a lot of people had never seen things like this before. Now it?s all over the country.?

And that is what is critical to Chihuly, who has helped to elevate the art of glass from a functional medium to a spectacular art form ? but that doesn?t mean it lacked validity in the past.

?Glassblowing has been around for 2,000 years, and it?s been a valid medium from the beginning,? Chihuly says. ?Is it valid as a medium for art? Somewhere down the line, long after we?re gone, someone will figure out what it was and how important it was. In the meantime, I get a great deal of joy out of people seeing my work.?

An Intricate Dance

Perhaps one of the most compelling aspects of glass sculpture is how it?s created. Blown in a studio using intense heat, a Chihuly piece is a finely timed and choreographed operation using an incredibly temperamental material.

?It?s all teamwork; the timing is essential,? says Trevino, who has seen Chihuly?s team in action. ?It?s like a beautiful dance sometimes, with a lot of energy and fire and all the molten glass. It?s incredible to watch. It?s also really intense, and a lot of pieces don?t survive. For every piece that you see here, there are probably at least half a dozen that don?t survive. It?s just the way it goes.?

Virtually anything can go wrong in glassblowing, and usually does. From blowing a piece too thin to improperly blending colors to getting the temperature wrong, there are a whole host of things that can lead to a glass sculpture?s demise. Even when a piece is seemingly safe and being cooled from its molten state to room temperature, something can go wrong and the piece will break.

?We have one artist who does some very big vessels, and he?s in intense heat looking down on the piece from a scaffolding that?s a couple stories up,? Trevino says. ?And if a drop of sweat would come down and hit that piece, it would shatter because of the temperature change.?

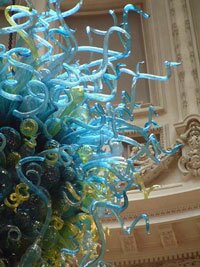

Then there?s the installation. Electric Blue was created specifically for the space in PISMO Gallery at Beaver Creek. First the space was modified from a small faux balcony to a massive, three-sided glass enclosure, then a photograph was taken of both the space and the village below and sent to Chihuly?s studio. Once it was completed, Chihuly took a photo of Electric Blue in the studio and dispatched two installers torecreate his vision 1,500 miles away at the base of a Colorado ski resort.

The boxes containing 300 individually blown pieces filled the entire gallery, Trevino says, but the excitement of seeing a Chihuly masterwork assembled before her eyes was worth the effort. And the fascinating thing is that the sculpture will never be assembled exactly the same way again. In fact, Chihuly himself likes to break down and reassemble an installation several times to make sure it all works before signing off and shipping it out.

?He likes to put them up, tear them down, put them up, tear them down, make sure everything looks good, over and over, and make sure it all works together. He?s a perfectionist,? says Trevino. ?He?s kind of a wild and crazy guy with his paintings; he?s very spontaneous. But when it comes to the technical parts of a lot of his work, the big work, he?s very particular and really wants to get it right on the money ? and always does.?

With several Chihuly works in the PISMO Gallery at Beaver Creek ? from smaller, $20,000 pieces to the nearly $300,000 Electric Blue ? the artist?s full spectrum of talents are on display. But the gallery also carries works by a broad range of other glass artists, from the well-known to new, up-and-coming talents ? artists who may have studied under or at least been influenced by Chihuly.

Having firmly achieved icon status, Chihuly ? one of only four Americans to have had a one-man exhibition at the Louvre in Paris ? is very much in demand these days. Not only are museums and botanical gardens clamoring for his works, but corporate and private collectors are increasingly requesting custom pieces.

PISMO owner Sardella says she recently helped procure a $200,000 custom chandelier for a private home in Evergreen. Again, photos were taken of the space and Chihuly worked with the owners to create an original work perfectly designed for their home.

?I think he?s extremely perceptive of what the client wants,? Sardella says. ?He?s always been very cooperative, and his people are very good at following up. He?s very professional and he is big business, but he?s still an artist. He?s very creative and very talented.?

Ever Evolving

As light spills in PISMO at Beaver Creek, changing the delicate, shell-like shapes and plant forms from dawn to dusk, Electric Blue easily entices passersby to step into the gallery and imagine the startling beauty of the gallery?s collection lighting up rooms of a private mountain retreat.

?What I like about all the various works are how different they look when you move them into various lighting situations; it?s always a different piece,? Trevino says. ?And they?re even more dramatic when you get them away from the rest of the collection here. When you put them in a home, on their own, it?s really unbelievable.?

That?s where Sardella sees a great deal of future growth in her ever-evolving relationship with Chihuly: Custom installations for homes. But she also eagerly anticipates new, original works for display at her various galleries, and says an exhibition in 2006 or 2007 at the Denver Botanical Gardens is in the works. Her Cherry Creek gallery would complement the exhibit with a simultaneous one-man Chihuly show, she says.

For Vail Valley residents and visitors, the collection of both Chihuly?s work and that of a multitude of other world-class glass artists in the Beaver Creek gallery is constantly evolving.

?The neat thing about the gallery is that we?re always very open to trying new things by the artists. They like to experiment a little bit and go out there and try something ? maybe a new technique, different colors, different shapes, whatever ? so we?re always excited to see what new pieces are coming in for the season,? Trevino says. ?It?s always a surprise. You never know what?s going to come in.?

For his part, Chihuly is satisfied that glass as an art form will flourish well into this century and beyond. ?As historic as it is, glass is a material for the 21st century,? Chihuly says. ?It?s certainly what we build our buildings with. It?s the material of the future. It?s also the least expensive material in the world and it?s the most plentiful material in the world.?

|

Leopard Spotted Basket Set  Spring Pink Persian Set  Macchia at the V&A  Chandelier at the V&A  Cinnamon Macchia - Studio Edition  Paris Blue Basket Set - Studio Edition |